Due to threats, this prominent social leader and former legal representative of the Association of Community Councils of the North of Cauca, had to leave his homeland for several months. Interview from exile with a man who resists and teaches others to do the same.

Written by: Daniela Mejía Castaño*

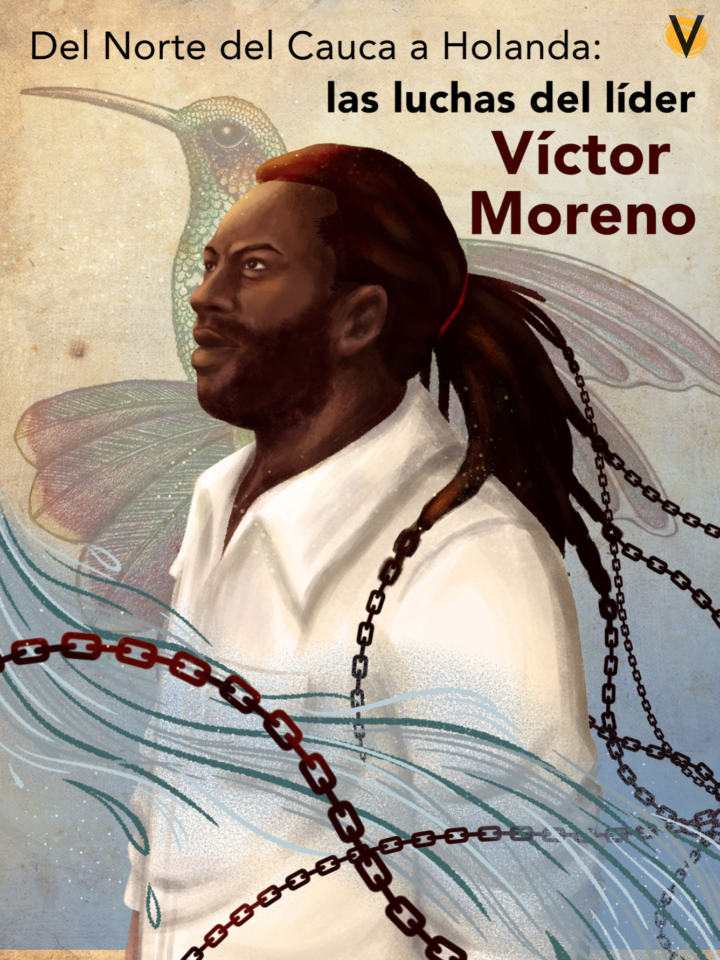

Illustration by: Angie Pik

Originally published by Vorágine (in Spanish)

Translated by: Lizzy van Dijk

-When I was twelve years old, I heard a story about a forest that caught fire, and all the animals started to run for protection. Mr. Owl was standing in a tree and looked from one side to the other, when a hummingbird caught his eye. The hummingbird went back and forth, back and forth. Mr. Owl stopped it and said: “What are you doing? In the middle of the flames everyone is running, even I am leaving, and you? what are you doing?”. The hummingbird replied: “I go to the river, take water in my beak and drop it on the flames”. The owl replied: “You’re crazy! Do you think the drops of water you’re carrying are going to put out the fire? Do you know what the hummingbird replied?” Víctor Hugo Moreno Mina asked me.

-What?

-“Obviously I’m not going to put it out, but I’m doing my part” That’s what the hummingbird replied. And that’s also what I’m telling you: I’m doing my part and I’ll keep on doing it until the end of this fire.

He gives me the answer, as a joke at the end of the interview, after having asked him why he does what he does: to defend the territories, cultural practices and productive projects of the black communities of the north of Cauca.

It is November 2020 and Victor is in the Netherlands, the country of bicycles, for almost three months. He is afraid to ride one though because the road signs are in Dutch or, at best, in English. Although this leader is an economist and has a Master’s degree in Government and Public Policy, he has forgotten what little English he knows due to the lack of using it, and he knows even less Dutch. However, he does speak another language that is strange at this time and in these lands: that of collectivity. “We are promoting community production projects”, he mentions; “in my territory we have collective ancestral practices”.

The city that welcomed him is Utrecht. This is one of the most important cities in the Netherlands, located on the banks of the Rhine River and home to one of the shelter houses of the Shelter City programme that welcomed Victor. It protects and supports human rights defenders from all over the world, relocating them to this picturesque city in the centre of the country to reduce the risk of assassinations and attacks against them, while giving workshops on meditation, international law and cyber security.

He entered the temporary Shelter City programme in September 2020 thanks to a Dutch friend living in Popayán, who heard that Víctor was stepping down as legal representative and senior advisor of the Association of Community Councils of Northern Cauca (ACONC) and saw it to be the right time for him to rest after 17 years of social work in one of the deadliest regions for a social leader in Colombia: the North of Cauca.

At first Victor did not want to come, but his Dutch friend insisted until he said yes and applied for the programme. “I can’t bear to leave my territory, not even to Bogotá or Popayán. Three days and I’m itching for it. The longest I had ever been away before was 15 days. Although I did have to live in Cali for a while due to threats, but I don’t see myself living outside of the territory”, he says in a meek, childlike voice.

The territory to which the leader refers and where he has lived since he was born, 34 years ago, is more than nine thousand kilometres away from Utrecht, in the municipality of Guachené and includes eight other villages in the municipalities of Caloto and Santander de Quilichao. According to the locals its lands were part of two haciendas, Quintero and Japio, which was owned by the slave owner Julio Arboleda Pombo. He was president of the Confederación Granadina, a republic formed by what are now Colombia and Panama, between 1858 and 1863.

Over time, some slaves who lived there paid for their children’s freedom. Others escaped subjugation and grew their own food in the forest – they were called cimarrones – and, little by little, these people united their lands until they became the Pandao Community Council. This associative figure, the Community Council, is protected by Law 70 of August 1993 and recognises the occupation by black communities of uncultivated lands in the riparian zones of the rivers of the Pacific basin, or of any part of the country.

According to the Geographic Information Systems (GIS) area of the National Land Agency (ANT), there are 204 Community Councils in Colombia, covering 5,733,002 hectares. ACONC, the association of Community Councils that Victor represented for seven years until March last year, groups 43 of them.

Although the figures are not entirely reliable. Elías Helo Molina, a researcher at the Observatorio de Territorios Étnicos y Campesinos of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana explains: “Not only does the SIG process official information but also the Directorate of Ethnic Affairs (DAE). It is a mess because the information from these agencies is very confusing since their information management areas sometimes have differences between each other. We have 352 requests from Community Councils for land titling that have not been attended to by the state.

In other words: Víctor is one of the most prominent social leaders of several black peoples of northern Cauca. Descendants of human beings enslaved by Spaniards and colonial elites who were liberated by maroonage and who in most cases spend their lives trying to get the state to recognise their lands, their rights and their cultures. Hence his temper, his non-conformity, his black complexion. Since 2014, he wears a horseshoe-shaped ring on the middle finger of his left hand to protect his life and his territory made with gold extracted from the earth by ancestral miners far removed from illegal and large-scale mining. He has his dreadlocks gathered in a ponytail on his back and speaks with clarity about racism, inequality and change.

A week before his return to Colombia at the end of November, during a virtual interview he gave to raise awareness in the Netherlands about the situation of social leaders in the Colombia, Victor had a breakthrough moment:

-In the short documentary you mentioned that you also faced many threats and even an attempt on your life, can you tell us more about the dangers you face as a human rights defender?”, asked Lizzy, his interviewer and one of his interpreters during his exile, in shy, foreign Spanish.

(Silence. Victor looks at the floor, bites his lips, searches for words, blinks, picks up momentum, slows down. He makes up his mind and answers).

Last year’s attack was not only intended to silence me and the other 15 companions but also to silence a process of social transformation, of self-government and self-administration of justice. A process in which we want to show the black communities that yes, we can (silence). Yes, we can (Victor looks up, his eyes moisten, he looks for strength, takes a breath and continues). Because the only thing that racism has done is to sow fear. And that fear has been transformed into stopping doing things, stopping living who we are, stopping living our own process, stopping our own cosmovision and only living for others. We put our labour and strength into other people’s companies; generating wealth. So much wealth that is generated in the north of Cauca is for others and our communities are increasingly impoverished.

Almost three months after that interview, on Wednesday 3 February 2021 at 5:42 pm, when on his way home from work, Victor received a text message threatening him and nine other social leaders from the north of the Cauca, for “keep being a snitch”. The threat, in which they were warned not to “think they are untouchable because they have bodyguards”, included the governor of the department, Elías Larrahondo Carabalí.

Now I am the one who asks him through a screen, a day before his return to Colombia – and before this new threat reached his mobile phone – what his thoughts are about leaving the Netherlands.

Every time I strengthen the idea that being in the organisational dynamic to help the black peoples of Colombia is worthwhile and is my life project. I’m not going to leave. With different protection measures, yes. I have to go around with three armed men and an armoured vehicle from the National Protection Unit (UNP). I can’t even go to the bathroom alone. My life has changed, I no longer have a social life, I can’t even go out with my friends.

According to the latest report published by Indepaz, 13 of the 79 massacres that were committed in 2020 occurred in Cauca. After Antioquia, Cauca has the most massacres. From an Afro-Cauca perspective, how can we make sense of the conflicts there?

The African diaspora and indigenous communities have been victims of human rights violations since colonial times. We arrived in America as slaves. We were always persecuted in order to exploit natural resources. Even after the abolition of slavery, private armies were sent to persecute us what later helped to take the land from the people with barbed wire. Then the violence came.

The black communities in the north of the Cauca were always liberal. The opponents, the conservatives, the police and the paramilitaries, who at that time were called “chulavitas” and “pájaros” (birds), killed black people. The elders of the community tell it offhandedly: “Ah, they killed so-and-so”, and it turns out that so-and-so was a leader.

This situation worsened even more towards 1930, when the idea of building the Salvajina dam was implemented. With this hydroelectric dam it seems that there was a plan to banish a part of the population that lived in the flat area of Cauca. The method was almost the same as that of the paramilitaries; they carried out massacres, burned houses and killed leaders.

Later, the so-called ‘green wave’ of sugar cane arrived in Cauca. The traditional Cauca farm had cocoa, coffee, bananas, maize and large, shady fruit trees which generated prosperity in the territory. This changed. The strategy was carried out through the Caja Agraria which gave mortgage loans only to those who would replace their cocoa and coffee plantations with soya and maize crops. These were products that were eligible for the credit line and which were, thereafter, produced on a large scale. People did not know how to work these crops and lost their crops, could not pay the debt, and their land was taken away from them. Those who came to buy it were the sugar companies.

It is the hillside and mountain areas where the black and indigenous communities are located that have been granted mining concessions to extract gold. They don’t touch the businessmen. They also need the territory to plant the tree that produces cardboard and to sustain the five free trade zones created by the Paéz Law, a law that was supposedly to help indigenous comrades and which ended up giving tax exemptions to new factories in the region. They make any excuse they can to make the north of the Cauca, a fertile land that can produce so much food, only a place where sugar cane grows while the communities around these companies live in total poverty.

Illegal businesses also play an important role as the black communities are also hit by the monoculture of coca leaf. The indigenous communities are even more affected by marijuana, coca leaf and poppy, which have encircled their food crops that provide them with their daily food. The government, however, only wants to fumigate with glyphosate.

And to all this we have to add the state’s desire for the black communities in Colombia to cease to exist. We don’t have to go very far to prove that: DANE (the Colombian Administrative Department responsible for the planning, compilation, analysis and dissemination of official statistics of Colombia) report in its statistics more than a million black people less than there actually are from the official statistics as if they disappeared by magic. This shows that we have no guarantees or protection, and that the state is physically afraid that we will be recognised as black people.

What are the beginnings of your leadership?

My paternal grandfather has always been involved in community and political leadership; my mother was a teacher, and I am the middle child. She was always more focused on the oldest and then the youngest. I was kind of adrift and I started to read a lot. At school we started a magazine, Ojo de Águila, and we ran the school newspaper as well. That generated leadership. When I finished school, we created Asocodita; an NGO to keep pushing forward the magazine from outside. We soon realised, however, that the needs of the communities were different. Since that year, in 2013, Asocodita did not publish a single issue again but helps the communities in productive projects, training, self-identity, entrepreneurship, work, study etc.

And then the first threats came…

Yes, since 2008, after the supposed departure of the paramilitaries from the territory where I live. Illegal mining began to spread in at least three rivers in the north of Cauca, until it reached the Palo river, which is in Pandao, my home. Tensions began to flare up. The river began to be contaminated with cyanide and mercury. The people who operated the yellow backhoes threw the banknotes like this.. look (he moves his hands upwards as if throwing a ball). This made even the indigenous people fight among themselves. Something that was seen before. Herein, also the black community was no exception.

Then, at dawn on the first of May 2014, the San Antonio gold mine collapsed which was the largest ever in the north of Cauca. They diverted the river and in its riverbed they made a ditch at least 200 metres in diameter and 50 metres deep. Some holes were even up to 100 metres deep. The river, looking for its mother, then soaked the earth and the whole thing collapsed.

When the police arrived they did not accept our authority as a Community Council. However, when they saw the people desperate for their families and unable to respond to the emergency, they called us. We had to mediate between them and the machine operators, who had already hidden the machines. We then tried to rescue people out of the collapsed mine.

I was the most visible face of that dialogue, so afterwards the miners approached me, as the regional authority, to give them permission to have that machinery there. I flatly refused, and together with the people who were resisting like me, we headed to the Guardia Cimarrona. Thanks to this Guardia, to the Guardia Indígena and the pressure from the community, we seized two machines without anyone’s help. Fifteen days later, I received the first threat from the Black Eagles, in which they mentioned two other comrades from black and indigenous communities. One of them being Feliciano Valencia. Later, in 2016, I had the opportunity to go to the peace dialogues in Havana and participate in the ethnic chapter of the Peace Agreement. Later, we participated in the mobilisation of the Agrarian Summit. From there came the attack against me and 16 other people, including Francia Márquez, in May 2019.

In regard to Francia Márquez, what has been the role of women in this struggle throughout history?

We cannot ignore the fact that we live in a macho society. It is not only in the black communities but also in the mestizo and indigenous communities. But when you do a little more research, black women have played a very important role. What Francia, Clemencia Carabalí and other women have done for black people is very important. In 2018, ACONC made a transition to the plan of Buen Vivir and the council went from 7 to 11 people. The assembly requires parity, so five women and five men. The other quota is given directly to an assembly of young people; and out of a thousand Maroon guards, I believe that around six hundred are women. In the daily work, the presence of women is stronger than that of men.

And how is ACONC’s relationship with the LGBTIQ+ population?

The authorities don’t talk about it. It is still a taboo for people. Obviously there are people from this population, but they are a bit hidden for fear of being ridiculed. Others decide to go to the cities to develop their personality. Paramilitarism increased the feeling of not wanting to say or talk about such things, they were punished. In addition, there are quite a few evangelical Protestant churches in the territory. I don’t even know why these issues are not talked about or worked on in the north of Cauca. Personally, I respect it and have no opinion.

You mentioned that you were part of the ethnic chapter of the Havana Agreement. It was hoped that violence in Cauca would decrease after the signing of the agreement but, although there has been progress, it is very little, how do you explain this situation?

Juan Manuel Santos himself put the brakes on the implementation of the agreements and once the ultra-right won, the corporate discourse was strengthened and more violent attacks came. I believe that behind this discourse is the search for the expansion of the economic development model.

It is no coincidence that the war is intensifying in the most productive territories: Caloto, Buenos Aires and Santander. Other places where most conflict is occurring is in the area where they want to build the Timba river dam in Buenos Aires; they make the excuse that it will supply drinking water to Jamundí and Cali and generate energy. These five free trade zones, the sugar companies, the mining and gold mining concessions, the dams and the oil deposits; if they move that… they need territorial control; land.

What I believe is that there is a concrete strategy of dispossession and banishment of the community in order to be able to carry out legal projects.

What model of economic development are you referring to?

Neoliberalism, which does not respect life, which only cares about money, and which confronts the very existence of ethnic communities and our own cosmovision of development where the priority is food security, growing our own food, relating respectfully with nature and with the different forms of life in the territory.

In addition, we have acquired some collective rights thanks to our organisational level and the traditional practices that make us black people. One can be of Afro population but not necessarily a black people because we have our own cultural practices.

Like what?

For example, the ritual when a child under the age of 7 dies in my territory is the bunde; drums that are played very loudly. Also, the way burials and wakes are conducted. Viche and aguardiente is then being distributed and the family is accompanied with anecdotes for the oral transmission of knowledge.

In our traditional festivities, the “fuga” is danced. This dance supposedly amused the enslaver, but this amusement ended with a dance to escape. If the dance was done just to amuse him, the juga was danced.

Even the way of fishing and cooking. Everything is different in each territory. What they do in Chocó is not the same as what they do in Buenaventura or on the Nariño coast. So when you simply become an Afro population in a city like Cali, for example, you are not going to be able to make the bunde, or watch over your dead for two nights. You become culturised and although you are black you become an ordinary citizen.

So the culture shock is not only because of the land but also because of the customs?

Yes, but above all because of the extraction of resources from the land.

I have heard that water is very important in the identity of the Community Councils, in fact, you organise yourselves politically according to the river…

Yes, this way of organising ourselves in the territory is reflected in Law 70 of 1993, which vindicates our organisational form from the time of the maroonage. All our houses and hamlets are around the river. In our case, we are organised by the micro-basins of the great Cauca River.

The paradox of living in the middle of rivers and not having an aqueduct…

Law 70 of 1993 makes special mention of the forms of production of the communities that you represent and that you have already mentioned: food security and sustainable development over profit, among others. These forms of production, seen from a neoliberal point of view, do not generate large profits. In that sense, one could argue that this way of life is not profitable?

I am an economist by training, but this form of production does generate life, oxygen and helps the different species of the planet to live, including human beings. Not only in the north of Cauca but in the whole world. So, what’s the use of money if they don’t have life?

Moreover, the accumulation of gold that they take out of the territory.. What for, to keep it? Gold is not eaten. So, are we destroying the balance of our system so that a few families in Colombia, and the world, can become richer? Wealth that is not even remunerated in the territory.

Colombia is a multi-ethnic and multicultural country, even our Constitution says so. There are a few who do not want to accept or respect these other ways of life.

Although Europe has large investments in environmental exploitation projects in other countries, also in Latin America, Europeans are just beginning to talk about circular economy and sustainability. However, they only do this among themselves and without mentioning their relationship with the investments they have in other countries. However, something is starting to change. Here in the Netherlands, the environmental organisation Friends of the Earth took the transnational oil company Royal Dutch Shell to court for being one of those responsible for the global climate crisis. Do you think this new “green consciousness” can influence the community you represent?

These are steps that help but they are slow and at some point these trials will also have to be articulated with our justice, the ancestral justice. I recognise that people are beginning to develop more awareness about what they eat, what they buy, who they buy from. But being here in The Netherlands, I have seen a level of consumerism where nature matters little.

In the future, do you see a world where regardless of ethnicity, development model and nationality, we respect nature?

Not really. That’s why they keep insisting on the viability of life on Mars. The colonial idea is planted. The problem is that if we lose the battle, it is not only an ethnic group that loses but the whole of humanity.

What has been the most difficult moment you have experienced in these 17 years of battle?

The first time I was threatened and the way I had to tell my family. I lived with my mother, her husband, my brother and some nieces. I had to wake them up at five in the morning, after praying and giving thanks, to prevent other people from telling them. I still shudder thinking of that memory. After that threat, the following threats only give me the strength to keep working.

And the most beautiful one?

I never thought about that (laughs). Maybe the recognition from some people in the community. In 2016 we held three social protests for which the opponents and the elites didn’t give a penny, but then the earth shook. In the largest mobilisation, almost five thousand people came out.

That mobilisation, which shook the earth, also made a journalist from Popayán ask publicly, as you said: “What do the blacks want, what messiah is leading them? Because the blacks only come to Popayán with outstretched hands asking for crumbs, asking for a job, asking for the scraps that fall from the table. But now they have risen up on the Panamericana to demand their rights”. Tell me, what do the black people of northern Cauca want?

That they accept that we exist, that we have our own justice system, our own health system, that we demand the protection of life of our ancestral territory and support for the implementation of our plan for Good Living (Buen Vivir). And that they help us in the dissemination of our struggle, of the consequences that we experience for defending life, of the productive projects that exist in the territories and in the creation of support networks so that when other leaders are being threatened we can get them out of the territory at least for a while.

Victor has to finish the interview and pack his bags for his return trip. That’s when I ask him why he does what he does and he responds with the fable of the hummingbird. He is eager. In Colombia, he says, an even bigger job awaits him than the one he did in ACONC. He wants to be the legal representative and senior councillor of the Pandao Community Council. A council he himself helped found in 2004 when his community was confronted by an outsider:

-It used to be Agropecuaria Latinoamericana but today it is called Incubadora Santander S.A. In 1998 they set up the largest egg production company in Colombia in our territory, 50 metres from the main school in the La Arrobleda hamlet. They were supposed to draw up an environmental management and social management plan in consultation with the community which to this day they have not done. On the contrary, what did happen after the arrival of the company was the constant harassment by the company against the community and the appearance of paramilitaries in the region. This brought us together and pushed us to create the Council. The brand that they market is Huevos Kikes.

-The one with the green logo? I ask him.

-The same ones.

The same ones I used to buy when I was told to “go for the eggs” and which I continued to buy as an adult. According to data from the same company, four million eggs are produced there every day which in effect makes it the largest producer in Colombia. By 2023, when they plan to increase their daily production by another four million, they project to have 1.5 billion pesos in profits.

-Well, now I’m back to face that situation and to represent fifteen thousand people grouped in ten thousand families that are part of the Council. And I have more news; we are strengthening our ethnic identity, and part of that work consists of recovering our African mother tongue. As we were unable to recover it, we are going to take the Palenquera language, from San Basilio, in the north of Cauca. The goal is to make it the second most spoken language in the department.

* Daniela Mejía Castaño is a journalist who graduated from the Universidad Javeriana. Since 2018 she lives between Colombia and the Netherlands. Her texts have been published by Baudó AP, El Espectador, Pacifista, Gaceta Holandesa and Vorágine, among others.